On Thakur Das’s farm in northern India, rice fields stretch into the distance, creating a chartreuse sea of waist-high stalks. Mr. Das, 59, gazed out at the crops on his small farm, about 16 kilometers from the city of Dehra Dun, where he grows rice, wheat and corn in rotation, as well as turmeric and beans. It looked to be another plentiful harvest. “Too much growth,” he joked.

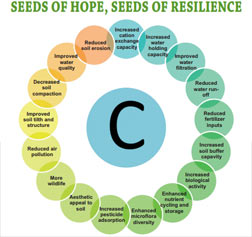

The bounty was all the more fruitful because Mr. Das’s farm, 10 miles from the city, is organic. He has not used chemical pesticides or fertilizers since 2002, when he joined Navdanya, a nonprofit biodiversity center and organic farm, a few kilometers away, to learn how to farm organically. Since he went organic, Mr. Das said, his crop yields, and his profit, have doubled.

Before Mr. Das switched to organic, one acre, or about 0.4 hectare, of land yielded 600 kilograms, or 1,300 pounds, of rice; now it yields 1,200 kilograms. He practices crop rotation and intercropping, or growing different crops together in the same field, and uses natural pesticides and fertilizer, like compost produced by worms.

“Organic is best benefit. Taste is different. Size of grain is bigger,” said Mr. Das. “Most farmers use chemicals. Soil is totally dead.”

In India, certified organic farming accounts for only about 1 percent of overall agriculture production, according to the Indian Agricultural Products Export Development Agency. Organic farming is still small worldwide, as well; it accounts for less than 2 percent of global retail production, according to the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization.

But as food prices rise around the world, agriculture has moved to the top of the global agenda after decades of neglect from policy makers and investors. India’s Green Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s used high-yield seeds, chemical fertilizers and irrigation to significantly increase agricultural production.