Our final week at the month-long A-Z of Organic Agriculture course on the Navdanya Farm outside Dehradun, India, concluded with an incredible education in Living Food. Once again we are grateful to all our guest speakers including, Dr Vandana Shiva, Anna Powar, Dr. Philip L. Bereano, Dr. Ashok Panigrahi, Kusum Mishra, Dr. Vaibhav Singh, Alison Caldwell, Dr. V.P. Uniyal, and Kiran Badhwar for their contribution and teachings on the science, politics, ethics and delicious cooking of true living food.

The week began with a great field trip to the diverse and local Sylvan Heights Biodynamic and Vedic Farm, followed by a generous meal provided by the Sikh community in Poanta Sahib. Back on the Navdanya farm participants celebrated Living Food with lectures on GMO’s and biosafety, food ethics, Navdanya fair trade, open pollinators, and climate resilience in an era of climate change. We also had wonderful cooking demonstrations on everything form herbal compounds to delicious forgotten traditional Indian dishes. Additionally, with so much heart and talent, meals were prepared by our participants, from Nepal to Italy, for a “zero-mile cooking” practical. In the field, the class thrashed rice, harvested turmeric, worked with seeds, mixed natural pest control recipes, worked with various compost techniques, and completed the A-Z of Organic Agriculture design project- a new campus garden built from the ground up. With incredible knowledge (and friendships) sown, we concluded our month-long journey of the Living Seed, Living Soil, and Living Food. As we closed, we planted a tree to honor the students unwavering dedication and contribution, and commemorate the first A-Z of Organic Agriculture course. Concepts were challenged and personal commitments to biodiversity and Earth Democracy were enlightened and redefined. Ultimately, students walked away with a life-changing experience and deep education in organic farming to take back to their own communities around the world.

Instead of patenting genetic discoveries and making them artificially scarce, we should draw on traditional farming practices

The great historian Lewis Mumford once described a patent as ‰a device that enables one man to claim special financial rewards for being the last link in the complicated social process that produced the invention‰. He was pointing out that we do not produce inventions ex nihilo, but rather draw on the totality of the inventions and knowledge that came before us.

It is no longer just the fruits of a centuries-long social process that are targets of patent claims. Through genetic engineering, corporations can now create and patent new life forms. Physicist Vandana Shiva, in a video launching the global Seed Freedom Campaign, calls this ownership of entire new species a form of slavery, and calls upon farmers and consumers to fight the privatisation of the genetic commons.

Could it be that she is being naive? Facing the spectre of world hunger amid continued population growth, maybe we will have to let go of our sentimental attachment to traditional farmers saving seeds, and transition to high-tech agriculture so that we can improve yields per hectare. After all, we cannot clear much more cropland at the expense of forests and wetlands. And to finance the enormous long-term investment necessary to engineer high-yielding, drought-resistant, pest-resistant varieties, don't we need to enforce a strong system of patents?

This position seems reasonable, but it is fraught with assumptions that collapse under close scrutiny. First and foremost is the notion that we need chemical pesticides, herbicides and genetically modified organisms (GMOs) to feed the hungry. Surely each new innovation brings higher crop yields, right? Surely yields are higher when you kill the bugs than when you don't, higher when you use improved strains than when you don't?

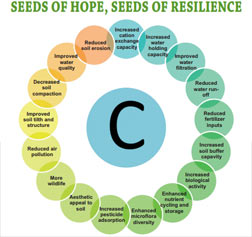

Not really. Holding all other variables constant, certainly a large wheat field will produce more if it is treated with chemical herbicides, pesticides and fertilisers. But organic agriculture, and especially permaculture and traditional peasant agriculture, don't hold variables constant at all. Each farming culture adapts over time to the unique characteristics of the local soil, biome and climate. Farmer and land co-evolve over generations. Numerous studies show that when organic agriculture is practised well, it can bring double or triple the yields of conventional techniques. With intensive intercropping on mixed permaculture farms, yields can be higher still. It is a myth that mechanised, chemical, GMO agriculture maximises yield per hectare.

What it does maximise is productivity per unit of labour, which is a good thing if we uphold American-style economic development as a model for the rest of the world. Taking the essential parameters of large-scale mechanised agriculture as a given, those who argue that we need genetic engineering ˆ and therefore GMO patenting ˆ to feed the world's hungry are right. However, these parameters encode assumptions that we are beginning to recognise as diastrous.

Western-style agriculture faces a mounting crisis that is insurmountable through the usual application of more control-based technology. Aquifer depletion, salinisation, soil erosion and soil compaction reveal our system as unsustainable. Meanwhile, each technological solution generates unanticipated new problems; for example, herbicide and pesticide resistance (superweeds and superbugs) mean that more technology is needed even to keep yields from declining. GMOs seem to generate unpredictable health dangers. And commodifying agricultural inputs like GM seeds and the pesticides and herbicides they are designed to accompany disrupts rural labour reciprocity, promotes indebtedness and creates dependence on volatile international commodity prices.

This crisis calls us toward more ecological farming methods that draw from the world's ancient agricultural traditions. These traditions include not only agronomic knowledge, but also social structures that allow that knowledge to evolve and circulate. Today, instead we have an intellectual property system that encourages innovation, yes, but only a certain kind of innovation ˆ the kind that leads to greater profits.

What is the alternative? The ancient practice of seed saving and seed sharing, which allows plants, land, and culture to co-evolve organically, is being revived by organisations like the Seed Savers Exchange. The Seed Freedom movement seeks to preserve this practice, which comes under assault whenever new regulations are proposed to require registration of all seeds to protect the intellectual property rights of patent holders.

Over the last two decades, innovative permaculture practices have spread like wildfire, and none of them are patented, made artificially scarce and then sold. Instead they are copied, shared and adapted to local conditions ˆ much the same way that genes spread through species and life forms spread around the globe.

In ecology, each species contributes to the wellbeing of all life and benefits from the wellbeing of all life. Now humanity is rejoining that circle. The next great agricultural transformation will not be an intensification of technologies of extraction and control; it will be an ecological agriculture that regenerates soil, aquifers and biodiversity. Traditional agricultural societies where farmers still save and share seeds are much closer to the ideal of ecological agriculture than the western model. Rather than imposing our technology on the rest of the world, perhaps it is us who can learn from them.