Biodiversity campaigner accuses corporate giants of trying to take over the world’s seed supply through genetic engineering

Ploughing a field and sowing seeds in Ethiopia, 2007. Photograph: Andrew McConnell/Alamy

Vandana Shiva shows no sign of fatigue despite an overnight flight from Delhi and an hour’s audience with Prince Charles before arriving at the Guardian, where she launches into her views on agriculture, food, biodiversity and “seed freedom”.

The Indian founder of Navdanya, which campaigns for biodiversity and against corporate control of food and seeds, says Africa is the battleground for two very different approaches to agriculture. One is the agroecological approach, based on the use of traditional seeds, diverse crops, trees and livestock, with smallholder farmers and the right to food at the core. The other is an industrial system based on monoculture, the use of fertilisers and genetically modified organisms (GMOs), where companies such as Monsanto, Dupont, Syngenta, BASF and Dow are dominant.

No guesses as to where she stands, as she accuses these corporate giants of wanting to take over the world’s seed supply through genetic engineering and patents by writing the World Trade Organisation’s intellectual property rights treaty. She quotes a Monsanto representative as saying: “In writing this treaty, we were the patient, the diagnostician, the physician – all in one.”

Shiva is no fan of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation either, which she accuses of pushing a vision of agriculture based on GMOs and the use of fertilisers. The foundation, which supports the Guardian’s Global development site, is one of the biggest players in agriculture.

The US will spend around $1bn this year on averting global hunger – but that includes supporting big farms – and, in 2009, the UK Department for International Development (DfID) spent around £20m. In the past few years, the Gates Foundation has invested more than $2bn in trying to help smallholder farmers in Africa and Asia out of poverty.

In Africa, the foundation funds several research organisations testing GM, and also Agra, the Nairobi-based Alliance for a Green Revolution, which aims to double the income of 20 million small-scale farmers and halve food insecurity in 20 countries by 2020. Although GM crops are allowed to be grown in only three countries, this is likely to change in the next five years.

Sam Dryden, head of agriculture at the foundation, told the Guardian in an interview last yearthat it lobbies countries to accept GM technology but that he is keen to see more investment in traditional breeding and staple crops such as sorghum, millet and cassava that have been largely ignored by big seed companies.

However, Shiva considers Agra to be making an assault on Africa’s seed sovereignty. “Agra by itself would have been insignificant. But because of Gates’s ability to leverage funding, Agra can have a big impact,” says Shiva, adding that Agra ambassador Kofi Annan is trying to win funding from the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation.

On its website, Agra insists it is not just an extension of big international philanthropies like the Gates Foundation, but an independent organisation with its own board and governance structure. “Our funding comes from a large number of international donors, but our base, approach and leadership are uniquely African,” says Agra.

Shiva’s fundamental argument against GMOs is that they represent a “petri dish” view that fails to take into account the complexity of the real world. “The idea that you can have everything in one gene is too crude to handle a complex living system,” she argues. “You can’t run away from systems thinking. GMOs represent an attempt to find an escape route, to think of one gene and then to move it.”

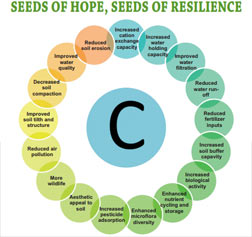

She also rejects the notion that it is possible to isolate a gene to develop a salt or drought resistant variety crop. “Say there are 1,500 climate resistant genes and we go to the gene bank to map drought resistant genes and make a bet on 100 varieties that have the highest potential. We still don’t really know what’s contributing to drought resistance. It is not a reliable way of finding drought resistant varieties. Diversity has to be the approach, there is no magic bullet. Diversity has to be our partner in adaptation and resilience.”

Besides, Shiva says, farmers in India have already developed drought tolerant varieties such as Nalibakuri, Kalakaya and Inkiri, and salt tolerant varieties such as Bhundi and Kalambank.

In her campaign for seed diversity, Shiva is pushing for groups across the world to preserve seeds – and her visit to the UK in February was part of that drive. She describes her movement as “open source seed”, a deliberate echo of open source software.

For Shiva, GMOs represent 20 years of failed promises and worse, leading to the emergence of super weeds and super pests. In India, Bt (Bacillus thuringiensis) cotton, sold under the name “Bollguard”, was supposed to control the bollworm pest, but according to a Seed Freedom report last year, The GMO Emperor Has No Clothes (pdf), the bollworm has become resistant to Bt cotton. On top of that, new pests have emerged and farmers are using more pesticides.

Climate change, argues Shiva, makes biodiversity even more crucial. “In a period of climate change, the world needs a biodiverse system,” she says. “The system of seeds based on monoculture is wrong and inappropriate. The biodiverse system has produced more food, and biodiversity means that seeds must be in the hands of farmers.”

Greetings from Hidayatullah Neakakhtar

Resource Centre for Development Alternatives

Faraz House, D-237, Ghazikot-Township

Mansehra 21300, Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa

P a k i s t a n

Tel: 0997 - 303601

Email: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

>Foster a Culture of Values-Based Organic Growth in Pakistan<