Technologies are tools for doing or making things. They are a means to transform what nature has given into food, clothing, shelter, means of mobility, means of communication. Technology is a means to an end; it is not an end in itself.

But when we stop perceiving technology as a means mediating between nature and human needs and elevate it to an end in itself, we falsely give it the status of a religion. The Green Revolution bred seeds to respond to chemical fertilisers — they were called “miracle seeds”. The father of the Green Revolution, Norman Borlaug, called the 12 people he sent across the world to spread chemicals by introducing new seeds his “wheat apostles”. This is the discourse of religion, not of science and technology.

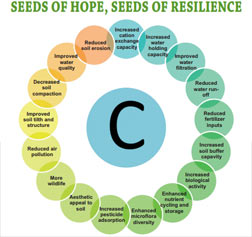

When the Green Revolution was introduced in India in 1965-66, no assessment was made of the impact chemical fertiliser will have on soil organisms, soil structure and the soil’s water-holding capacity. No attempt was made to compare the yields of Green Revolution varieties and the outputs of indigenous varieties and mixed farming system. When we started to conserve native seeds through the Navdanya movement in 1987, we found many of the indigenous varieties outperformed the Green Revolution varieties in grain yield. They also outperformed them in total biomass yield — this really matters because while the grain is eaten by humans, straw is food for soil organisms and farm animals. Our work on mixtures and biodiverse systems of farming shows that as a system, indigenous biodiversity produces more food and nutrition per acre.