“Creating food insecurity: an analysis into the structural and policy factors increasing food insecurity in India”

Press statement

The food crisis of hunger and malnutrition in India is a reality we can no longer ignore. It is the face of the underweight children dying of starvation; it is the face of the farmer who committed suicide, unable to feed himself and his family with dignity; it is the face of every common man and woman, who come back from a market with empty bags, as food is too expensive. And the food crisis doesn’t stop here: India hasn’t only emerged as the capital of hunger, but also as the capital of diabetes.

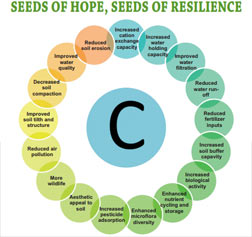

Economic, political and social globalization of recent years has had a massive impact on both our food systems and the way we eat. Agriculture, the principal scope of which was providing food, has become an instrument of trade; food itself has become an instrument of trade. Over the centuries, Indian farmers have developed the capacity to produce food for sustenance, for feeding their families, and for marketable surplus while also respecting the environment, as it is that very Earth to provide them with life. These traditional systems were productive and sustainable, and most importantly, they made India a food sovereign country, a country that could feed itself.

Today, we can’t call ourselves a food secure country, and food security is a matter ofnational security. Trade oriented, industrial and chemical agriculture pushed by foreign and domestic corporations alike is steadily undoing what people achieved through years of struggle, what Gandhi so strongly advocated, that is self-reliance. Once sovereignty over the food system is lost, the entire debate on food security loses meaning. In India, this is exactly what is happening: we are losing sovereignty of production to agribusiness, sovereignty of distribution to the private sector, and sovereignty of consumption, more and more manipulated by aggressive marketing strategies of junk-food producers.

This is the other face of the crisis: Indians aren’t only eating less, they are eating worse.Our culinary traditions are not only culturally relevant; more importantly, they are tailored to fulfill our specific nutritional needs, different across populations. The massive bombardment of junk food ads, with snacks and drinks sold globally is drastically altering our dietary choices, with a tendency especially for the better off to consume processed, packaged fast foods that have zero nutritional value and add to the incidence of diet related diseases. India has emerged as the capital of diabetes; it has also witnessed an increase in obesity, hypertension, high cholesterol etc.

The hunger and the other malnutrition crisis are both outcomes of mistaken approaches that undo rather than ensure food security: if we think of it in terms of availability, access and intake, we realize that the Indian problem is not one of lack of food, but of lack of entitlements to it. This is manifest in the fact that the producers are hungry, in the fact that while children starve, food rots in our warehouses. The food crisis that we are facing could have been avoided, and can still be addressed, if only we are ready to identify its real causes and apply real solutions, not palliatives: the food crisis stems out of the loss of sovereignty over our food system, increasingly controlled, dominated and manipulated by powerful external actors perpetuating their own agenda, and on their agenda there’s profit, not a hunger free world.

Further, policies such as the US-India Agriculture Knowledge Initiative (which was signed along with the U.S.-India nuclear agreement and has on its board multinationals like Monsanto, ADM and Wal-mart) and the blind promotion of genetically engineered crops (in spite of the failure of Bt cotton and the debt trap it has put farmers in) have further eroded our food sovereignty and food security. The Government is putting forward the Food Security Act; however this act totally ignores the root causes of hunger. Worse still, it deliberately leaves untouched the structural roots of the malnutrition crisis.

It is for this reason that we have sought to put together a comprehensive review of the structural and policy factors that have led to the crisis: by studying the international dynamics that laid the foundations of it we recognize the root of the problem, consistently ignored in policy discourses, while by analyzing the politics of food we get a chance to finally choose the right policies to tackle the crisis effectively, as it is possible to do so.

The report ranges from Independence till today, reviewing the most important structural changes in the Indian economy and the policies implemented in relation to agriculture and food security. While following Gandhi’s preaching on self-reliance together with struggles for land and tenure security such as the Thebaga movement brought India closer to self-sufficiency and food sovereignty, the policies followed mainly after economic reforms of the 90s have steadily undone the country’s sovereignty over its systems of production and distribution.

The liberalization of Indian economy following the WTO and World Bank diktats based on the free trade myths of efficiency, productivity and consumer benefit along with the domestic adoption of the New Agricultural Policy focused on privatization, intensive industrial agriculture and agricultural technologies such as GMOs and hybrids affected the Indian countryside in a dramatic manner. The opening of the most employment generating sector to trade and the entry of agribusiness both Indian (such as Reliance and ITC) and foreign (Monsanto ADM etc) has led to the creation of monopolies in agrarian markets, leading to the displacement of million local producers.

The spate of farmers’ suicides of recent years is a direct consequence of this unsustainable system: debt creating agriculture locks farmers into a spiral of expensive inputs, crop failure and low returns to farmers when profits accrue exclusively to multinational corporations. The case of Monsanto and Bt cotton in Andhra Pradesh is one of the most shocking examples of this, where the company pushed its GM cotton promising yields as high as 1,500Kg per acre, and instead delivering only 200Kgs. Crop failure added to farmers indebtedness, when the debt was originally created by the expensive purchase of agricultural inputs such as seeds, fertilizers and pesticides from the very same company. The failure of Bt Cotton in Andhra cost farmers losses of Rs 1 billion.

Even more worryingly, this dramatic trend hasn’t been halted but rather favored as the Government of India steadily deregulates unfair, non-transparent and unaccountable corporations while imposing more and more constraints to local farmers: from a policy point of view, the Amendments to the Indian Patent Act, 1970 in order to comply with WTO TRIPs, poses the biggest threat to India’s traditional knowledge and trade balance of payments. In fact, under TRIPs everything from a seed to a plant can be patented by privates to charge huge royalties, while farmers rights to conservation, sharing and saving of seeds is turned into an intellectual property crime! The only ones set to gain from this change in Indian laws are MNCs; companies like Monsanto, ADM and Wal-Mart are not only increasing their presence in the Indian market but also lobbying aggressively for a change in the domestic regulatory framework to suit their business needs. Their presence on the board of initiatives such as the U.S. IndiaAgriculture Knowledge Initiative, 2008, reveals the shocking power of foreign private actors in shaping Indian agricultural policies; it goes unsaid that this road is one towards corporate profits, not democratic food security.

Indian policymakers along with citizens need to be vocal against the progressive corporatization of Indian agriculture and food systems. This process is happening all round, undoing our country’s food security: the privatization of seeds, industrialization of production processes, deployment of aggressive marketing strategies and entry of mass retail chains such, all by the hands of few global corporations are threatening not only Indian producers but consumers as well. While on the one hand we find displacement resulting in the loss of livelihoods of the million Indians employed in agriculture, mandi workers, small retailers, artisan processors etc, on the other we are witnessing to a shift in consumption patterns leading to the scary increase in the lifestyle/food related diseases that were typically of the West, such as obesity, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases etc. India has emerged as the capital of hunger, scoring worse than Sub-Saharan Africa in the Global Hunger Index with one million children dying of malnutrition every year, and as the capital of diabetes, with the number of diabetic patients in India having more than doubled from 19 million in 1995 to 40.9 million in 2007, and projected to increase further to 69.9 million by 2025.

It is in this context that the Food Security Act currently discussed by the Parliament cannot be accepted as a solution to the food crisis, but is instead offering the disease as the cure: the policy review laid out that India’s food problem is one of lack of entitlements, not of lack of food. The fact that as a country India is losing sovereignty over its food systems translates in livelihood insecurity: if food is no longer a right but a commodity, it becomes functional to purchasing power, not a matter of entitlements. This process leaves the country hungry even when warehouses overflow with grains and food rots in go-downs.

The current practice of maintaining high buffer stocks without distributing grains through the Public Distribution System, curtailed since 1997 in the name of efficiency to only targeted beneficiaries, is resulting in both human and financial losses. The Government has often recurred to imports of staple items like wheat from corporations that sell at much higher prices compared to local producers; simultaneously, it is exporting grains at below poverty lines prices or less, while the country starves. MNC representatives threaten to withdraw from the Indian market unless buffer stocks are reduced, pushing for an increase in imports that raise their profits while worsening India’s terms of trade.

This is yet another consequence of the corporate led changes in domestic regulations: the removal of quantitative restrictions under WTO. The case of Soya-bean importsto replace adulterated mustard oil in 1998 was nothing but one of the instances where corporations stood to gain from the destruction of the local industry, by dumping unsafe and low quality products rejected elsewhere into the Indian market; this resulted in a surge of imports up from 2,36,000 tonnes in 1997-98 to 8,00,000. The reliance on other countries or giant agribusiness for food crumbles the entire notion of food security: the biggest blind spot in policy discourses is in fact the neglect of sovereignty, or freedom to produce, distribute and consume food in a manner that is nationally coherent.

The Food Security Act itself fails by limiting the entitlements to the BPL households, when the BPL is itself very reductive, secondly by reducing the entitlement from 35kg as per the Supreme Court interim order to 25kg, thirdly by failing to account for nutritional needs and last but not least by proposing the replacement of Public Distribution to the poor with corporate coupons. Truth is, all coupons will do is increase multinational turnovers while reducing public investment in social welfare, worsening the hunger and malnutrition crisis. If in the present system food has become a commodity, hunger has become a commercial avenue for private profits.

Food is too expensive as a result of the whopping inflation on basic consumer items, and inflation is substantially the outcome of the integration with monopolized global agricultural markets and forceful “free” trade; it is also more unsafe as corporations push their GM products and processed junk foods onto Indian consumers; it is less nutritious as none of the Central initiatives even account for minimum nutritional requirements.

All in all, the result of corporatization of food systems from production to distribution and consumption is food insecurity: when even producers are hungry, how can citizens be better off? How can children be guaranteed a healthy meal, when the Government devolves responsibility to the private sector?

Food is too sensitive a need to be treated as any other tradable commodity. Addressing food insecurity needs changing the policies that create hunger. Keeping the hunger creating policies intact implies creating hunger by design. The need of the hour is shifting to a decentralized, democratic and sustainable food system that recognizes the farmer as key producer; a system that is bottom-up and acknowledges farmers, women and villagers as primary custodians of food security, for food security starts at the household level, in the hands of the common man and woman.

Hunger can be eradicated before 2020, if the political will is present and the State committed. If not, the numbers of hungry, malnourished and sick people will only keep growing, and our nation will be doomed by shame, not shine.